RO-008_BREMEN_BUNKER

Conversion and roof- extension of a World War II Bunker into a house for a family of four

(Text Quotes: Bunkers are leftovers of the war … Architecturally they represent a pragmatic approach to building, fascinating and depressing in their functionality – beautiful and ugly at the same time. They are holes, cast into concrete and planted into the urban fabric. Forever…. Ideas to penetrate the concrete mass, to carve it out, to cut holes into the green block, to play with the 3-dimensionality of the existing versus the light weight structure, we were allowed to build on top, inspired the design process. A compact three-storey house plugged into another three-storey structure describes the basic configuration.

In June 2002 good friends of ours bought a three storey World War II Bunker in the middle of their favourite quarter of Bremen, Germany, in order to convert and extend it into a house for themselves and their two children. Their idea was to build a two-storey ‘penthouse’ on top using this massive structure as a plinth for their new home. This bunker is not a cellar buried in the ground as often imagined, but a big concrete block, 25 x 10 metres on plan, 8m high above the ground imitating its three storey neighbours. The site was chosen, because in this old and well-established part of Bremen no empty plots of land exist anymore. A conversion of the common and available typology of the Bremer-Style-House, which is similar to the English terraced house, would have limited the freedom to challenge conventional domestic arrangements and perceptions of space drastically.

It was the wish of the clients to live central and urban, but being able to walk around their house as usually possible in a suburban or countryside setting. They dreamed of views and sunlight and being ‘closer to the sky’. They wanted space, space to breathe, the feeling of having space, but without actually needing a lot of rooms and without wanting to build a huge expensive palace. They are ‘obsessed’ with light, but the bunker had no daylight at all. The site and the bunker together with the client’s ambitions provided us with some interesting contradictions.

The bunker with its 1.1 metre thick walls has three storeys; two and a half above ground level, while the lowest one – the basement - is build half into the ground. Its rough concrete inside with several smaller scale rooms, low ceilings and neon light generated the opposite impression than its completely overgrown and therefore green and friendly outside. Appearing as an out of scale hedge this green block disguised itself (again) very successfully. Bunkers are leftovers of the war, a reminder of horrible times, filled with memory of death and disaster. Architecturally they represent a pragmatic approach to building, fascinating and depressing in their functionality – beautiful and ugly at the same time. Most of them are owned by the state –as this one until a year ago –and many of them remain unused. There is a certain attraction to inhabit these leftovers, niches, commercially not viable, unthinkable and well-hidden spaces. They are holes, cast into concrete and planted into the urban fabric. Forever. And some of them might even grow…

Starting to share the fascination of our clients we quickly convinced them to not just build on top of this green hill, but to use and incorporate the space inside the bunker to a whole concept of living in and on top of it.

Ideas to penetrate the concrete mass, to carve it out, to cut holes into the green block, to play with the 3-dimensionality of the existing versus the light weight structure, we were allowed to build on top, inspired the design process. Questions arose about how a highly insulated and compact space could inhabit a cold and quite uncontrollable mass like the bunker. Where to draw the line between the outside and the inside was a crucial decision to the developing concept. A strategy emerged in which part of the house occupies part of the existing structure -like an inlay, insulated from inside, ‘eating’ its way through to the surface and the light - and connects through the roof with the ‘penthouse’ space built on top. A compact three-storey house plugged into another three-storey structure describes the basic configuration. We tried to get the most out of this space without filling it up with new structure, however, aiming to use and dramatise its mass, its size and its roughness.

The size and position of the holes, which we cut into the walls and the massive roof, had to respect the mechanical constraints of the diamante-saw cutting procedures and had not to jeopardize the structural integrity of the building. Planning Regulation Law prescribed a maximum outline of the visible extension, while new and strong energy saving regulations forced us to work with high quality and therefore expensive materials. At the same time the budget asked for a small and compact building and an inexpensive construction method.

the design:

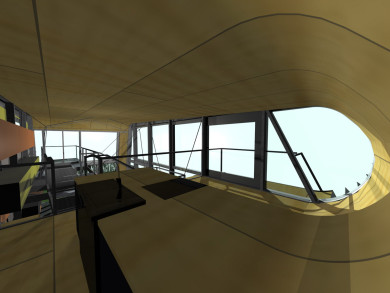

One enters the house via the existing main entrance to the bunker on the mid level. A third of the floor of the top storey has been removed, allowing the light from the new large opening in the roof and through the new stairwell to reach the entrance level. At the same time it offers stunning views of the house inside the house the moment you enter through the heavy metal door (view 1) The existing staircase connects to the upper bunker floor, where the new structure starts. A steel gallery bridges over the hole in the floor, leading to the entrance door of the warm part of the house. The new staircase hanging down from the steel structure above completes the transition from dark to light along the new cut through the 1.6meter thick concrete roof (view 2).

The linking element, giving the house on top its campervan type shape is an approximately 33 metres long facade-roof-floor-wall. This element, timber clad from the inside, fulfils many functions. It starts inside the bunker, climbs through the hole and another story up, separating the most private bedrooms and bathrooms from the open stair and living areas, bending over to form the kitchen floor, folding over at the north end to serve as curved wall, then roof and finally south façade towards the garden (view 3). The main living areas are one spacious and open hall with loosely defined zones with different characters.

The cooking, sitting, dining area overlooks the whole inside space like a cockpit as well as the adjacent roofs. A gallery made out of steel mesh cuts through the main double height space (view 4) and penetrates the garden facing façade to form a balcony capturing the best river views. The main bunker ‘hall’ stays raw and exposed leaving room for future extensions and providing a playground for more ideas and big performances and parties.

A deeper discussion about domesticity might reveal or consider the driving factor behind this effort for being so different and for expressing individuality through architecture and the home in a very critical way. But we ignored this loaded territory of domestic dreams and the social and sociological implications of their fulfilment, purposely focusing only on the playful exploitation of all offered difficulties and constraints. Guided by enthusiasm about the spatial opportunities and understanding the economic constraints as a helpful hand not to overload the design, the brief seemed like a conundrum promising pleasure and joy in finding its ‘solution’.

As one discovers thoughts while writing and designs while drawing, all four of us have more ideas than before while building. Besides having more ideas on how to design the house, we also have more ideas how one could live … - in it.

Photos/CGI : RecOrt